Spreading The Plague: The Perfect Hollywood Ending

Act 1: My writing partner, Teal Minton, and I decide we want to make a horror

film. In our opinion, most of the great horror films had been done years ago

and almost all of them dealt with fears that existed in society; fears that

still resonate today on a very primal level: the communist scare that feeds

the original INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS; a woman's sacrificial

role in society and household so terrifyingly represented in ROSEMARY'S BABY;

a parent's inability to help or understand what is happening to their adolescent

child in THE EXORCIST. These films terrified us. They left us thinking, asking

questions and looking inward.

Act 1: My writing partner, Teal Minton, and I decide we want to make a horror

film. In our opinion, most of the great horror films had been done years ago

and almost all of them dealt with fears that existed in society; fears that

still resonate today on a very primal level: the communist scare that feeds

the original INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS; a woman's sacrificial

role in society and household so terrifyingly represented in ROSEMARY'S BABY;

a parent's inability to help or understand what is happening to their adolescent

child in THE EXORCIST. These films terrified us. They left us thinking, asking

questions and looking inward.

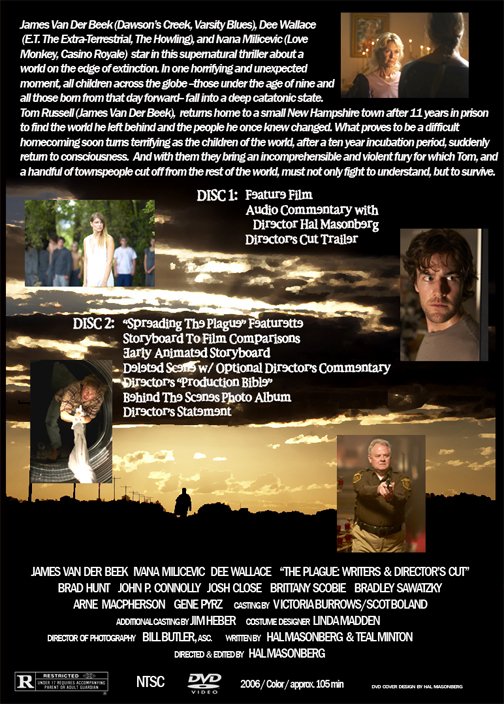

So we write THE PLAGUE: a story about kids and violence in society, on fear, and how we react to it. We tell it through the guise of a horror film about how our main characters react when faced with a world where all children become catatonic, then wake up and strike out against them. Like all good films, these characters are the emotional backbone of the story.

We shop the script around for five years looking for people who don't want to turn it into a teenage slasher pic. Meanwhile, the script's themes become more and more relevant: the massacre at Columbine happens, 9/11, the war in Iraq... For a while, this scares people away from the script, "We love it, but we can't make it here. It's too timely, too sensitive. But let us know if you get it made cause we'd like to see it!" Even our agents suggest we shelve it and move onto something more commercial.

Eventually we end up at Seraphim Films, Clive Barker's production company. They love the script and want to make it. There is only one stumbling block for us: THE PLAGUE is nothing like a Clive Barker film, nor is it meant to be. The producers assure us that the reason they want to make it is precisely because it isn't. " Clive Barker makes Clive Barker films," we're told. It's explained to us that they want to create an avenue for smart, adult horror films of all shapes and sizes. They use the Clive Barker produced GODS AND MONSTERS as an example: more a character piece than a horror movie.

This is exactly what we've been looking for: people who understand the film and want to make it.

Act 2: Through the next three years of development, the script gets even better; we are all excited about the film we're making. We join forces with Armada Pictures, a production company that puts together the money. It's agreed by all that we will take the film, once completed, out to film festivals where it can find its audience and a domestic distributor. We know this film is more character-driven, more psychological than most of today's mainstream horror films; this one's not geared toward your typical horror fan and will therefore require a distributor who embraces this and can successfully get the film out to its intended audience.

With our cast in place and the script in great shape, we head up to Winnipeg, Canada to shoot THE PLAGUE. We're barely off the plane, when we find out that Armada has pre-sold the film to Screen Gems for domestic distribution. Normally, this would be cause for celebration, but the sale is done in such a mysterious way that we find ourselves asking the basic question, "Does Screen Gems want the same film we do?" But we're never given a straight answer and there's little time to argue; we're a few weeks from shooting and knee-deep in pre-production. We hope for the best, tell ourselves it will turn out great, that Screen Gems will be the perfect home... And move forward.

It's

a grueling, wonderful, 20-day shoot and by the end, the producers are thrilled. "This

is better than anyone expected!" I'm told repeatedly.

We wrap and head back to L.A. for post.

It's

a grueling, wonderful, 20-day shoot and by the end, the producers are thrilled. "This

is better than anyone expected!" I'm told repeatedly.

We wrap and head back to L.A. for post.

I ask one of the Seraphim producers to be in the editing room with me; I want Clive's interests represented. He does and his input is both helpful and insightful. We have six weeks to put the film together. During this process, I start to notice some of the other producers acting a bit cold, distant. One of the producers confides, "[Someone at the top] wants this to be a different film. And if they get what they want, it's going to be everything we've been fighting against. It's going to be horrible."

I rush to my agent's office with the news. "You shouldn't be worrying about

this

kind of stuff now," he says. "You should be enjoying editing. It'll all

work out."

But it doesn't. Tensions are high, everyone's on edge, worried. We finish a rough cut. It still needs work, but you can see the film now, it's coming together. I ask the Seraphim producer, "You think Clive will like it?" He smiles, "I can't imagine what I'd do if he didn't."

Clive doesn't. Or so I'm told. I'm not present at the screening, per the producers' request. I'm told Clive feels it's too slow, not gory enough.

"I don't understand," says one of the producers about Clive. "It's as if he'd never read the script."

But he had. I attempt to contact Clive, to get more details, but my attempts are met with resistance. We never connect.

People who I'd worked beside for three years suddenly become indignant. Others, who I had grown to consider friends, grow quiet and step into the shadows so as not to jeopardize their careers or position.

The day my contract ends, I walk into the editing room and one of the producers I've worked beside for three years says to me with frightening matter-of-fact casualness, "We're cutting down the characters and turning this into a killer-kid film." Everything stops.

"Why would we do that?" I ask. "We've worked so hard not to have it be that."

He looks at me, condescending, "Because this is a horror film called THE PLAGUE, not THE TOM RUSSELL STORY" (Tom Russell is the film's hero).

It's explained to me that they want more blood, less character. My stomach turns. The thing I'd most feared, the thing I'd fought 8 years to prevent, was happening: THE PLAGUE was on its way to becoming another horror pic about plot and action, not characters and theme. I argue that this is not the time to change course; that the characters are the film's emotional core; that if the audience doesn't care, they won't be scared. But it's too late.

For the next few weeks I call the producers, but my calls go unreturned. I go to the editing room and am met with verbal abuse beyond anything I have experienced before. I even offer to help the producers with their cut of the film in the hope that I might salvage something: one moment, one sequence, one small tidbit of the film we'd made. I write up a series of editing notes and suggestions, only to see them tossed aside. The producers are very clear: "This is our film now and we see no reason for the writers and director to be involved."

The door is shut. The betrayal I feel and the loss of the film is agonizing.

Of course there are no "support groups" for filmmakers who have

essentially "lost their babies." So how does one cope with this kind

of situation, with this particular brand of pain and loss? I ask myself, "What

do you want? What is most important to you?" If it's to keep working and

making money, then I should probably do what my agent and lawyer vigorously

recommend: "Let it go. Move on."

Of course there are no "support groups" for filmmakers who have

essentially "lost their babies." So how does one cope with this kind

of situation, with this particular brand of pain and loss? I ask myself, "What

do you want? What is most important to you?" If it's to keep working and

making money, then I should probably do what my agent and lawyer vigorously

recommend: "Let it go. Move on."

But what if what's most important to me is to tell stories, to grow as both an artist and a human being, to reach people on some deeper level... What if the thing that is most important to me about making this film is this film ?

Well, shit, that would be inconvenient.

"I'm going to finish my film."

My reps look back stone-faced, not amused. When they realize I'm not joking, they spin into a tizzy, tell me it will be a career-killer. "I can't imagine anyone who would want to see your cut!" Maybe so, but my gut tells me otherwise; to fight this hard, to invest so much of myself psychologically, creatively, physically and then have the film taken away and turned into the very thing I was making it in reaction to...

I need to finish it. And it will have an audience. If only my friends and family, then so be it, but someone will see this film. Hell, I want to see it! I fight the overwhelming desire to pack my bags and leave L.A., and instead take the digital dailies I have on DVD (the film was originally shot in Super 35 by the extraordinary Bill Butler), and transfer them into Final Cut Pro on my Mac laptop and start editing the film from scratch.

I spend the next six months in self-imposed exile. I teach myself effects, sound design, I create a temp score. And this time, unlike the 6 weeks I'd spent in the editing room previously, I really get to study the dailies. I know every frame, every actor's nuance, every angle, every breath. I start to see not only the film we'd written, but more important, the film we'd shot . I experience a new "intimacy" with the movie; something I never want to work without again. Here's more joy, more excitement, more passion. Here's why I wanted to make films in the first place. Here's the little boy with his super 8 camera!

The last thing I expected when I was kicked off this film was that I would discover something greater than if I had remained on board.

I finish the film and show it to the people closest to me. The response is overwhelming: people who would never have gone to see a horror film otherwise are asking to see it again and again. Lovers of classic horror films are asking if they can have copies to show their friends. My friend Carrie jokes, "The reason they took your film away is because you made a horror film for 40-year old men and women with masters degrees and the producers didn't know what the hell to do with it!"

I show the film to some of the cast and crew and they are ecstatic. They agree that this is the film we set out to make. This is the film they want seen!

I send a copy of my cut to Screen Gems. I have no idea if they ever look at it.

The producers' cut is released straight to DVD in September 2006 under the title CLIVE BARKER'S THE PLAGUE. The film has been completely restructured, stock footage added, new dialogue recorded. Even Bill Butler hasn't been invited to color-time his own work. My name is still attached as director, Teal and I as writers. It feels like a wound reopened. For us, the film in no way reflects our vision, work, or intent.

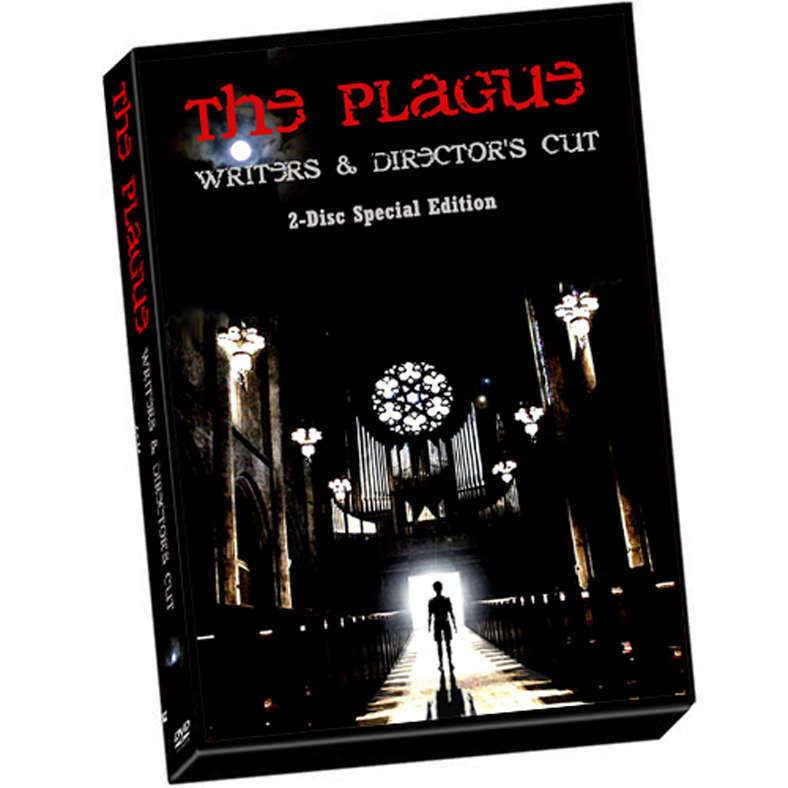

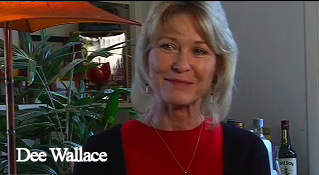

Act 3: Legally, I can not show my cut at the local multiplex or release it

on video, so I make a documentary called SPREADING THE PLAGUE in which cast

and crew members, film authors/journalists, speak out about what I now call

THE PLAGUE: WRITERS & DIRECTOR'S CUT. They openly discuss what they love

about the film, why it is important to them to have it seen. I create a website

by the same name: spreadingtheplague.com and put the doc up for all to see.

I include articles, trailers, interviews. Thousands of people log on. Other

sites start writing about what has happened. I start a petition and link it

to the site in the hope that Screen Gems will agree there is an audience for

this cut and release it as it was meant to be. People immediately start to

sign.

Act 3: Legally, I can not show my cut at the local multiplex or release it

on video, so I make a documentary called SPREADING THE PLAGUE in which cast

and crew members, film authors/journalists, speak out about what I now call

THE PLAGUE: WRITERS & DIRECTOR'S CUT. They openly discuss what they love

about the film, why it is important to them to have it seen. I create a website

by the same name: spreadingtheplague.com and put the doc up for all to see.

I include articles, trailers, interviews. Thousands of people log on. Other

sites start writing about what has happened. I start a petition and link it

to the site in the hope that Screen Gems will agree there is an audience for

this cut and release it as it was meant to be. People immediately start to

sign.

And people are still signing.

The story of THE PLAGUE -both onscreen and off- is one of fear and how we react to it. I believe it was fear that allowed the film we made to be turned into something it was never intended to be. Fear of being wrong, of losing one's job, of doing something different. And Post-production can be the most frightening (as well as the most exciting) part of filmmaking. It is also the most important time to stick together. Communication is essential. To toss the writers and director aside as if they had nothing of value to contribute is, in my opinion, a grave mistake, but one that happens far too often in our industry. It is when the creative team and the business team work together, with mutual respect and understanding, that great films are made. But it is in moving past those fears and doing what is best for the film that allows this to happen.

So it is my continued hope that we can do just that: move beyond the egos, the doubts, and the fears that have plagued this film, to deliver the movie we made to the audience we made it for. Now wouldn't that be the perfect Hollywood ending?